The Coval Years: 1981-2012

“…if I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” - Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

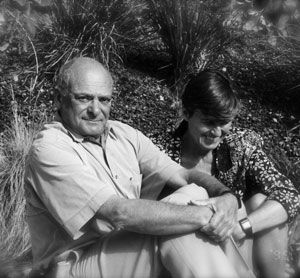

Harriett Sumerwell sold her estate to William Wuerch in 1979, who had hoped to subdivide and develop the property into about twenty lots. Wuerch chose not to proceed, and put the estate up for sale in 1981 with the subdivision incomplete. Two years earlier Barbara and Myer Coval had moved to Vancouver, British Columbia hoping to establish a home there, but an unusually wet winter left them feeling discouraged with the city and they ventured south to Seattle to look at potential properties in Puget Sound. Myer was a Canadian citizen at the time who had grown up in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Barbara a German citizen, and since neither had family ties to any particular city in the Northwest they were open to many possible locations for their home. They were at first looking at waterfront properties, and when nothing resonated with them their realtor suggested the Starr Estate. When Barbara saw the property she knew immediately that this was their future home. The grounds were identical to her native Germany’s Streuobstwiese, or meadow gardens, and she saw the potential of both the house and the estate grounds. After years of moving around the country and Europe pursuing research grants, the Covals had finally arrived to a place they could truly call home.

The journey of the Coval family began in the Ukraine in the small village of Sgriotza, near the city of Kishinev between the Dniester and Dnieper Rivers, now present day Moldova. In the early 1900’s Myer’s great uncle had managed to escape the impoverished conditions there and made his way to Winnipeg, Canada, where a strong Jewish community had formed. In the late 1800’s Jewish laborers from the Ukraine were enlisted to build Canada’s first transcontinental railroad, and after the turn of the century railroad projects were still going strong. Myer’s grandfather soon followed his brother and found work with the Canadian Pacific Railway building bridges over the new rail system. Once he had settled he sent money to move his wife and children to Canada, but as they made their way from Sgriotza to Odessa on the Black Sea to board a steamer to Canada, World War I broke out and they had to return home. The family had to find what little food and work was available, and Myer’s father, now eleven years old, was the family’s primary breadwinner, operating a team of horses by day and helping to smuggle people from Russia to Romania by night. Eventually the war ended and the family received money to head to Canada, six years after their first attempt, but by then four of the six children had died. All that remained was Myer’s grandmother, his father and his aunt.

Once in Canada, living conditions were much improved, but still tough. Myer’s father worked in a bakery and later began a small store in Kanisota Falls, just barely making ends meet. In 1920 Myer’s mother arrived from Russia where she was living near the Polish border. She had suffered a similar fate of being stranded in Eastern Europe before World War I broke out, and witnessed much of the carnage of war. Her mother had died of the flu, and so the young 16 year-old girl made her way to Canada with her siblings. It was there that Myer’s parents met, eventually marrying and raising three children.

Myer was an avid reader, and was getting tremendous encouragement from his parents to take his education seriously. His mother was a very good student, but opportunities never presented themselves, so the best she could do was encourage her children to do what she could not. As a child Myer had read two books that would set his life course, Sinclair Lewis’s “Arrowsmith” and Rene Vallery-Radot’s “The Life of Louis Pasteur”. Both books inspired the young Myer to dream of a life of medical research and improving the lives of other people. After high school in 1943 he attended the University of Manitoba where he received a BA in Liberal Arts. Later he found a research opportunity at the University of Toronto, developing techniques to more accurately measure the potency of insulin, and while there he earned his MS in Biochemistry. Myer began to seek further research opportunities, moving over the next few years from projects at Berkeley, Stanford and later Brandeis University, where he earned his PhD. in Biochemistry. Myer along the way had gotten married to a woman who had survived Auschwitz, and shortly after he arrived in Dallas, Texas for his next research project, his marriage had ended.

In Dallas Myer secured a grant researching enzymes at the University of Texas Southwestern Research Center. The head of Myer’s research department was from Germany, and believing that the Dallas area lacked skilled lab assistants, arranged for young research graduates to come to the United States from Germany, with all travel expenses paid to and from and a required two years commitment in the States. When one of the young women arrived to the Dallas airport, Myer was asked to pick her up and bring her to the lab. It was Barbara.

Barbara Sixel was born in 1938 and grew up in Kaiserswerth, an ancient town on the outskirts of Dusseldorf, Germany. Kaiserswerth’s history goes back to 700AD, when Saint Suitbert established a monastery at Werth, an island and strategic crossing point on the Rhine River. Barbara’s grandfather was raised in the Mosel River Valley at the turn of the century where he learned farming, and as a young man he took his skills to Kaiserswerth, where he managed and worked a large Protestant farm. His wife was a stern, imposing figure that taught delinquent children at the Protestant school nearby, and together they raised four children on the farm, three sons and a daughter. Barbara’s father Konrad also pursued farming, earning a diploma in agriculture, and when his father was seriously injured in a bicycle accident, Konrad took over management of the Protestant farm at age 26 where he also lived. While at the farm he married and had a son and twin daughters, all who participated in the duties of maintaining the crops and tending to the cows, pigs, horses. For Barbara life on the farm was enjoyable and stimulating.

In Diezenkausen, a small village consisting of ten farms and thirty homes, Barbara settled into a happy life as a teenager. There was plenty of food, with gardens producing potatoes, beets and an abundance of fresh milk. Barbara and her twin sister Elka took up tennis and skiing, which they would develop into a lifelong competition between twin sisters. Barbara also spent time in the woodworking shop of her uncle who built furniture as well as skis. At age 16 she attended Haushaltungsschule, a two-year domestic arts program teaching the skills of cooking, sewing and cleaning, and then attended Frauenfachershule, a “domestic science college” that continued her domestic arts education as well as specific focus on chemistry and physics. Barbara then moved on to the University of Applied Sciences Fresenius in Wiesbaden when she completed a two-year program for lab technicians, and then worked at the University of Freiburg as a lab assistant to Professor Goedde. It was in Freiburg that Barbara learned of an opportunity to see the United States while working in Dallas, Texas for two years. The prospect was exciting, seeing a new country while earning money at the University of Texas Southwestern Research Center under Professor Daniel Harris, and still having a prepaid ticket back to Freiburg, a city she very much loved. Without any more deliberation, off she went to Texas.

Now in Dallas, Barbara appreciated Myer Coval’s help in navigating her new surroundings, and in time a friendship developed and they eventually married. In 1967 they gave birth to their first child Judith, and shortly thereafter the family moved to the Bay Area in search of a better work opportunity. In Montclair the Covals bought their first home, a custom-designed house built in 1940 and featured in Sunset Magazine the same year. The house was on a lot wooded with mature firs, and the open plan of the living space had two fireplaces and lots of built in cabinets. The interior walls were finished in knotty pine, and Barbara and Myer remember the warmth of the wood with fondness. While in Montclair the Covals added three boys to the family, and in time the research grant ended, and the growing family was yet again looking for a research opportunity.

The next research grant brought the Coval family to Switzerland, where Myer’s work with the Red Cross focused on making Immunoglobulin G (IGG) in a form that was safe for patients. The grant project was to last ten years, but after twelve months the research center in Switzerland believed the project had no merit and withdrew the funding, leaving Myer and his family with no income. Myer had faith in his research however, and he left Switzerland with the work he had begun and returned to San Francisco. Without peer support for his work and few financial resources, Myer set out to prove the validity of his observations. He met a fellow researcher, Bob Wichmann, who offered to share his lab, and friends and family loaned Myer money to support his family while he worked. During the day Myer worked on a road crew for five dollars an hour, and Barbara started selling fruit and vegetables out of their garage to make ends meet. After six months working in Wichmann’s lab Myer’s research was successful, and after securing patents for the production process he began looking worldwide for pharmaceutical firms to produce it. Ultimately the Green Cross in Japan showed serious interest, and after 2 months of trial production there, Myer returned with a contract providing for the distribution of his product in Japan. The successful marketing of IGG would change not only Myer’s life, but also the lives of thousands of patients who would benefit from the drug itself.

With the worldwide negotiations of IGG largely behind them, Myer and Barbara set out to turn their new Mercer Island house into a home. Initially they retained a series of architects who proposed grand designs that either tore down the existing Starr house or retained little of its charming character. Uneasy with such an abrupt approach to the remodel, they instead chose to live in the house and absorb the qualities of what attracted them to the home and grounds in the first place. Slowly a design approach began to emerge, one that encouraged the family to take a more direct and immediate hand in shaping their environment. Myer had come across Christopher Alexander’s landmark book “The Timeless Way of Building”, a passionate treatise on designing a home that draws inspiration from the lives of the inhabitants, not from the detached proposals of a designer who will never live there:

“At the core … is the idea that people should design for themselves their own houses, streets and communities. This idea may be radical…. but it comes simply from the observation that most of the wonderful places of the world were not made by architects but by the people”.

Myer and Barbara shared the spirit of Alexander’s ideas, and found confirmation in the approach through their many travels around the world, in which they experienced countless old structures that were “designed” with simplicity and honesty. The essential quality of this approach to building, of letting the land, materials and sensitivities of both the inhabitants and craftsmen shape the home became the guiding principal for what followed over the next sixteen years.

As the Coval home developed in this unusual yet timeless way visitors would find themselves deeply moved by the emotional experience of the place, but could not find an explanation for the warm, inviting feelings the spaces invoked. There was no dramatic elements, no latest trends, nor pretension to impress. As Christopher Alexander would suggest, the home has a “quality without a name”. Efforts were made to keep the house anchored in the landscape with a horizontal profile and extensive glazing with views into the gardens. Interior spaces were remodeled to suit the Coval’s needs, yet the inherent structure was never violated but rather upgraded and added to. The best possible materials were sought out, not for their expense but for their beauty and longevity. And as craftsmen and artists began to accumulate on the site, the Covals honored their experience and skill by letting them contribute significantly to the shape of the home. The craftsmen did not mindlessly build what a set of drawings or the whims of the owners dictated. Rather, there was an ongoing creative conversation with Barbara and Myer, in which the collaboration yielded results that no one had imagined. The home was a reflection of process, of interaction, and of discovery.

By 2000 the creative conversation began to quiet, and the Covals settled into the serenity of place that was begun by David Alexander 100 years earlier, and nurtured by the Starrs along the way. As researchers, Myer and Barbara valued process and knew that method of work and integrity of material is everything. The collaborative journey of discovery, the joy of wonderful materials, the maturing of skill and sensitivity, these were the qualities that mattered. The home itself is a reflection of something extraordinary that happened, and fortunately for everyone, a rather beautiful reflection. It remains full of possibility and potential, waiting for it’s next creative journey, and the Covals would want it no other way.